Please, Resist Racial Essentialism

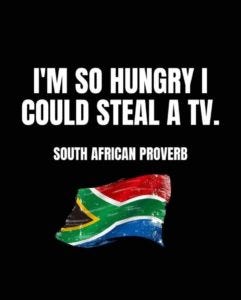

There are many reasons for heartache right now. You probably already know what they are. In Gauteng and in KZN, lives have been lost and livelihoods have been destroyed as areas are looted. The situation in Durban threatens to devolve into a race war. To call it ‘unrest’, or even a ‘riot’, is to put it too lightly. It is closer to an attempted insurrection. It is anarchy and chaos. Supply chains have been disrupted; highways have been barricaded. Residents face food, medicine, and fuel shortages. Businesses big and small have been burnt to the ground, and many won’t recover. We’ve witnessed inconceivable loss. Meanwhile, citizens have formed armed vigilante groups to protect their property and their communities, and are racially profiling people in the process. Some stores (those that are still open) are doing the same. For the people living through this, questions about why this is happening are secondary to questions about how to respond to it. Speculating about causes is, to some extent, a luxury that people caught in the centre of this do not have. Survival comes first. Given this, I’m not writing to weigh in on the causes of this situation, a topic on which a lot of insightful analysis has already been written. Instead, I want to make a plea, to friends, to community members, to whoever’s reading this: please, resist racial essentialism. By racial essentialism (or racialism), I mean the idea that certain traits/capacities are innate to certain racial groups. Under this view, the values and behaviours of a subset of a group are considered representative of the whole group. Such analysis leaves little room for the role of things like class, gender, culture, religion, and individual identity. In principle, racialism is distinguishable from racism, as racism goes further in asserting the superiority of one group over another. In practice, racialism almost always nets the same conclusion. I think this distinction matters because there are people who don’t consider themselves to be racist or to hold racist beliefs, but who nevertheless rely on racial essentialism to make sense of the world. For example, one sometimes hears from members of the Indian community that Indians have found economic success in South Africa solely because they ‘work hard’. On the surface, this sounds fine. While it implies that large and diverse populations act with a single intention, which strikes me as logically incoherent, the belief itself seems innocuous. But in context it seldom is, because the silent implication is that others (specifically Black people) work less hard than Indians, that “they” are lazy, and that this is why the majority of people in this country live in poverty. This might sound like a leap. It is a leap! But it’s a leap that people make all the time, sometimes without noticing. I have heard it from elders, from people my parents’ age, and most alarmingly, from people of my generation. Besides being morally repugnant, this belief is frighteningly ahistorical. It ignores the the numerous policies and strategies the Apartheid government used to make life harder for Black than for Indian people. It pretends that we exist in a vacuum, that we do not live in the shadow of the past. As people have been plunged into survival mode, as tensions escalate and an “us-vs-them” mentality dominates, racial essentialism has framed how many people understand what’s going on. While it seems people that participated in the looting can be divided into at least three groups - ‘pro-Zuma loyalists’, ‘opportunistic criminals’, and ‘desperate people using this as an opportunity to finally put food on their tables’ - those who think in essentialist terms seem to flatten these different groups into one. Thus we end up with things like this uninspired meme.

There are two strong reasons to reject racial essentialism. First, as in my examples above, it typically entails racism. This is by design: these beliefs are the product of decades of Apartheid-era governance, of a state machinery that created an explicit and baseless hierarchy between racial groups. While such beliefs have been internalized by many of the people who lived through Apartheid, and have been passively inherited by some of the people in my generation, we should not lose sight of their unholy origin. Second, it is overly reductive. Racial essentialism provides a grossly inaccurate way of understanding the world. It permits no nuance: a crime by some is considered a crime by all. It leads people to think that all Black South Africans deserve to suffer, as if an entire population group ought to be held liable for the actions of a minority. It obscures more than it reveals. This is true regardless of the race of the person making essentialist claims.

*

Like everyone, I’ve been blindsided by the events of this week. I have no idea how cities and towns will rebuild. At this early stage, 'no one has a decisive grasp on the situation...all information is limited [and] all attempts to make sense of the crisis [are] provisional'. There is some cause for optimism: I’ve taken heart from the efforts I’ve seen on social media to coordinate donations, to organize clean-ups, and to support one another. But my optimism is eclipsed by my fear that we are sliding backwards, that the racial animosity this crisis has dredged up will take decades to dissipate. I don’t have any easy answers. Probably there are none. The one thing that seems clear to me though is that if we are to avoid perpetuating Apartheid, if we are to keep in sight the intrinsic dignity of every South African and the possibility of a future that is just and inclusive, we must resist racial essentialism. We must strive not to accept simplistic, prefabricated narratives, just because the more complicated truth remains elusive. We must remember our history. In times of social upheaval, radical change is possible. This is as true of political systems as it is of personal beliefs. So, though it may be futile to try changing the minds of others, now is as good a time as ever to try.